|

| By Tony Sagami |

As the son of a vegetable farmer, I was acutely aware of seasons; spring was one that brought a mixture of blessings and curses.

“Spring” meant baseball, and my family loved America’s pastime. All of us — especially my father and my sister — were darn good baseball players.

However, “spring” also meant planting season, extra chores, after-school work and weekends full of long, laborious hours.

|

One of my earliest spring memories on the farm was picking rocks. I spent hundreds, maybe thousands, of hours on my hands and knees picking up stupid rocks when I was in grade school.

As I grew older, I started to help with de-winterizing farm implements, spreading fertilizer, tilling the soil and, of course, plantings.

Another spring event I could count on almost like clockwork was seeing my father in a suit.

My father was deeply religious, but only went to church twice a year: Christmas and Easter.

It wasn’t that he lacked faith — there was just too much farm work that needed to be done to feed his family of five.

My father wore dungarees and threadbare flannel shirts 363 out of the 365 days of the year, but he proudly wore his only suit when he went to church.

Taking the Church Suit Out of the Closet

I distinctly remember one spring when I was eight or nine years old. I saw my father in his suit. But it wasn’t Easter, and it definitely wasn’t Christmas.

“Why are you dressed up, Daddy?” I asked.

He said he was going to the bank.

The bank?

Almost every spring, my father would shave, dab some Vitalis in his hair, put on his church suit and go to our local bank to ask for a loan to buy seed, fertilizer and fuel.

Honestly, farming doesn’t pay much, and my father struggled with low wholesale prices, rising costs of seed and fuel and the negative cash flow between spring planting and summer harvests. But, if the weather and crop prices cooperated, he would return proudly in the fall to pay back the loan in full.

|

If not, he’d ask for an extension, his head hanging in shame.

Unfortunately, the bad summers seemed to outnumber the good ones, so my father never made a lot of money. Making ends meet was always a struggle.

My classmates laughed at my hand-me-down clothes and logger boots I wore. But I never went to bed hungry, and my mother kissed me goodnight every night until I left for college.

Farm work was hard. And I hated it — I mean, I really hated it — at the time. But I believe those years on the farm taught me valuable lessons about investing.

Lesson No. 1: Summer Profits Come From Winter Efforts

My non-farmer friends assumed farmers took it easy during the winter. Wrong!

Even when snow covered the ground, my father still worked at least 12 hours a day. There may not have been any crops to harvest in winter. But there was always plenty of off-season work to do on the farm, such as repairing the farm machinery and mending fences.

My high school basketball coach used to scream at us that our winter games are actually won during the offseason workouts.

The same is true of farming … and investing. You make your profits before you buy a stock, not after you sell it.

It is just like rock picking in the spring when I was a toddler. It seemed boring and meaningless at the time. But every successful business needs a strong foundation, and the basic building block of preparing the soil is crucial.

Lesson No. 2: Core and Explore

The most important decision any farmer makes is what to plant. The price of vegetables could vary widely from year to year, and many farmers would play a “Green Acres” version of roulette by trying to anticipate what the “hot” vegetable of the year would be.

Not my father; he stuck to red radishes and green onions for roughly 80% of his farmland and gambled with the last 20% of our land on what crops he thought could deliver big payoffs.

|

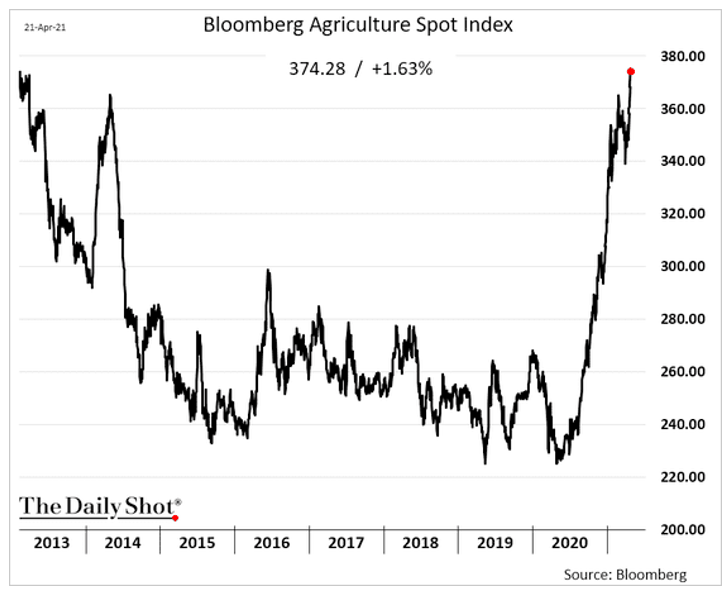

By the way, prices of agricultural products are soaring, and the entire food chain — from fertilizer to seed to farm machinery to food producers — is making a mountain of money. This could be a great time for you to explore by adding some agricultural stocks to your portfolio.

But keep the majority of your portfolio in solid, boring, established, consistently profitable blue-chips and limit how many dollars you invest in potential home-run stocks.

That’s exactly the strategy I follow in my Disruptors & Dominators newsletter service.

Lesson No. 3: Cheap Is Better

What makes one farmer more successful than the other? My father knew it isn’t how much you harvest, but how much profit you make on what you do grow.

My father was a very frugal man, so he seldom bought anything if it wasn’t on sale. And he never had to hire a mechanic, an electrician or a plumber because he could fix anything — and I mean ANYTHING. His operating cost was lower than most other farmers.

I’m a cheapskate, too, so I seldom buy stocks unless they go on sale. In fact, the first thing I do every morning is take a look at the 52-week low list. Almost all the stocks that wind up on the 52-week low list are there because they’re horrible stocks. But some of them are dealing with short-term problems instead of long-term fundamental flaws.

Coda

I’m sad to say my father died 12 years ago at the ripe old age of 93. He never made a lot of money. But he lived a long, healthy, admirable life, and he saw all three of his children become successful professionals.

My career was always a mystery to him, though. He said my hands were as smooth as a woman’s, and he never owned a share of stock in his life. Whatever money he saved always went into his bank account.

But he was madly proud of his three children. And I will forever thank him for working us like dogs on the family farm. That hard work made us who we are today.

Best,

Tony Sagami