|

| By Tony Sagami |

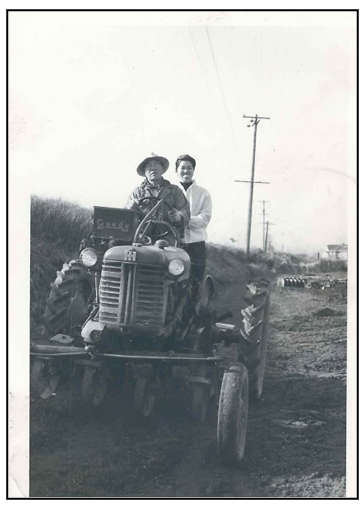

Around this time of year, my father would put me to work the minute I came home from baseball practice. And I hated it.

If you’ve been with me for a while, you know that I was raised on a vegetable farm in Western Washington.

My parents were hardworking vegetable famers, but making ends meet was always a struggle. My classmates laughed at my hand-me-down clothes and boots with holes in the soles. But I never went to bed hungry, and my mother kissed me goodnight every night until I left for college.

Farm work is difficult. So difficult that I hated it as a youth, but I now think that those years were the foundation of the success I enjoy today.

Moreover, there’s a surprising number of investment lessons that I learned as the son of a farmer. Here are six that come to mind …

No. 1: Boring Work Is

the Most Important Work

Farming is far from glamorous, and most of the work my parents had me do was dreadfully boring.

When I was in kindergarten, my father would have me pick rocks out of the fringes of the farm. In the summer, I spent thousands of hours on my hands and knees pulling up weeds. It was boring and seemed meaningless at the time, but every

successful business needs a strong foundation, and the basic building blocks of preparing the soil are crucial.

The same is true of investing. Reading annual reports, financial statements and balance sheets can be boring, but it is that fundamental, time-consuming research that sets you up for long-term success.

No. 2: Summer Profits Come

from Winter Efforts

My non-farmer friends assumed farmers took it easy during the winter. Wrong!

Even when there was snow on the ground, my father still worked a minimum of 12 hours a day. There may not have been any crops to harvest in winter, but there was always plenty of off-season work to do on the farm, such as repairing the farm machinery and mending fences.

My high school basketball coach also used to scream at us that December games are actually won during off-season workouts. That carries over into the investment world. You make your profits before you buy a stock, not after you sell it.

No. 3: Core & Explore

The most important decision any farmer makes is about what to plant. The price of vegetables could vary widely from year to year, and many farmers would play a “Green Acres” version of roulette by trying to anticipate what the hot vegetable of the year would be.

Not my father; he stuck to red radishes and green onions for roughly 80% of our farmland and gambled with the last 20% of our land on what crops he thought could deliver big payoffs.

I do the same with my portfolio today. I keep the vast majority of my portfolio in stable, established blue-chip companies and use the last 20% or so for more speculative bets.

Click here to see full-sized image.

No. 4: Profits, Not Revenues

What makes one farmer more successful than the other? Many of our neighboring farmers also grew radishes and onions, but what made my father more successful was that he knew it isn’t how much you harvest, but how much profit you make on what you do grow.

My father was a very frugal man, and he seldom bought anything if it wasn’t on sale, so his cost was lower than most of his competitors’.

I’m a cheapskate, too. So, I seldom buy stocks unless they go on sale. You’ve probably heard the warning, “Don’t try to catch falling knives.”

Well, I love falling knives.

No. 5: Plow Under

Your Mistakes

Sometimes things just went wrong on the farm. Insects would infest our crops, some months were so wet that it triggered mold outbreaks and some years frost would come early and damage the crops.

Instead of spending too much time and/or money on rescuing the damaged crops, my father would often plow them under and start over.

My father was a big believer in cutting your losses and moving on. I find that many investors are too stubborn to admit a mistake or want to wait until they break even before selling. Don’t take that risk; instead, cut your losses and move on.

No. 6: Expect Storms

Whether or not my father had a good year depended on three things: (1) no late frosts, (2) no early frosts and (3) no natural disasters like hailstorms, droughts or insect infestations.

While you can’t avoid disasters, you can plan for them and run for cover when they arrive. The wise investor diversifies in anticipation of those things that are beyond his control and buys insurance to protect against catastrophic losses.

That is pretty wise advice for the current market. If you’re so heavily invested in stocks that you’re losing sleep, you are NOT diversified enough and should consider either increasing your allocation to cash or purchasing some portfolio insurance.

Best wishes,

Tony

P.S. Your loyalty to Weiss Ratings deserves VIP treatment and concierge services. If you want more of our investing research and writings, and you are one of our elite users of more than one service, please click here to see how our Partners can benefit.