|

| By Nilus Mattive |

As you might know, I spent more than five years working for Standard & Poor’s back in the early 2000s. And during that time, I learned a lot about the company’s various equity indexes.

Originally, these indexes were simply designed to measure the stock market’s performance.

That all changed when Vanguard’s John Bogle did a licensing deal with S&P back in 1976 to create the very first passive mutual fund based on the company’s S&P 500 Index.

The idea of buying and holding a wide range of representative stocks rather than trying to outperform the market through active management was pretty revolutionary back in 1976. Because it entailed less fees, it also proved rather unpopular on Wall Street.

Today, index investing is big business, especially since widely followed experts like Warren Buffett consistently say most people are best served by them.

Indeed, State Street’s SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) is now the largest and most traded fund in the world, with roughly $540 billion invested.

Overall, there are now more passive funds — both mutual funds and ETFs that target all types of various indexes — than I can even list succinctly.

Great, right?

Well, in my opinion, that has actually created a new problem … a hidden danger that most investors simply don’t recognize at all.

A Quick Look Under

the S&P 500’s Hood

The whole point of index investing has always been very straightforward: You get a well-diversified portfolio of important stocks in one fell swoop.

Put another way, you don’t have to figure out which company is the next big thing because you probably already own it.

Except that isn’t really true, especially with the S&P 500.

As its name suggests, the “500” contains 500 of the most important LARGE stocks in the U.S. market.

How large?

To get added to the index, a company must have a market cap of at least $18 billion.

Of course, once it’s in, it doesn’t automatically drop out if it goes below that threshold.

That brings up another interesting point — unlike members of the Russell 2000 index, which are strictly determined by a set of rules, S&P 500 constituents are added and deleted by a committee.

In addition to the market cap requirement, other factors include trading volume, liquidity and where the company’s revenues come from (at least 50% must be earned in the U.S.).

Committee members also use a little bit of their own judgement, deliberating about which companies provide the best overall measure of the large-cap stock market as a whole.

That fact has created its fair share of criticism. For example, many pundits questioned why the committee waited so long to add Tesla (TSLA) to the index.

There have also been bigger problems with the index’s human element, too.

In 2020, a member of the committee was charged with insider trading for telling someone when companies would be added or deleted from various indexes.

On the heels of that scandal, there were also allegations in a Bloomberg article that some companies were paying S&P for ratings in the hopes that would help them get chosen for the index.

Of course, my big concern has to do with the way the index itself is constructed.

While the S&P 500 contains 500 companies, those constituents do not have equal representation mathematically. Instead, the bigger the company’s market cap, the greater its effect on the index’s performance.

In practical terms, that means investing in an S&P 500 index fund is hardly giving you the type of diversification you might expect … especially at a time when so many investors are pouring more and more of their money into a handful of high-flying technology companies.

Obviously, nobody is complaining about this right now. It’s actually what’s been causing the S&P 500 index to post such eye-popping gains. But don’t take my word for it.

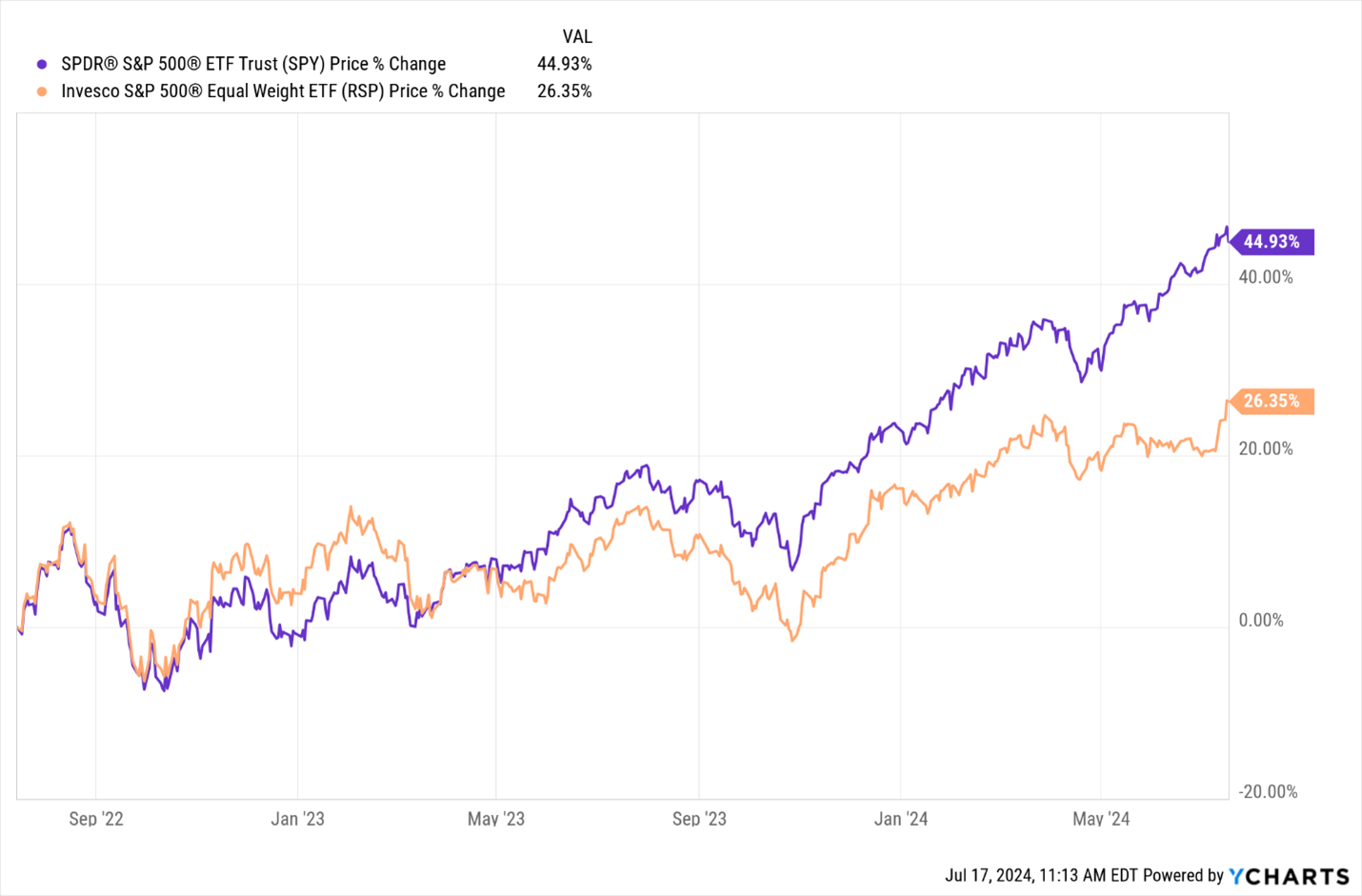

This chart compares a regular S&P 500 index fund — the SPY — to a version that weights each individual component equally — the Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (RSP) — over the last two years …

As you can see, the regular version nearly doubled the performance of its equal-weighted peer.

Now consider how much influence just a few companies have over this “broad” stock market index. Here are the top 10 components and their respective percentages in the SPY …

As you can see, eight of the top 10 components are tech companies. Meanwhile, a ninth — Berkshire Hathaway (BRKB) — also has substantial exposure to tech, with roughly 44% of its equity portfolio invested in Apple (AAPL).

All told, S&P data shows that roughly 33% of the index is currently allocated to the technology sector.

What’s more, just those top three names — Microsoft (MSFT), Apple and Nvidia (NVDA) — account for about 20% of the index.

Again, that’s great when everyone is bullish on those companies.

However, it’s a sword that cuts both ways.

Back when I worked for S&P, there was a tremendous difference between the 500 index and the tech-heavy Nasdaq.

And back then I also watched the Nasdaq implode when investors soured on the tech sector.

So, if you’re currently invested in index funds, pay attention to what you actually own and what type of diversification you’re actually (probably not) getting.

Best wishes,

Nilus Mattive

P.S. Fortunately, there’s a new way to invest without relying on your own stock-picking skills or a broken index. Click here to see how to beat the S&P 500 even as that index gets further and further away from its stated goals.