|

| By Mark Gough |

It’s a fight almost as old as the U.S. itself: Federal versus states’ rights.

Where authority resides regarding any regulation is a complex and often touchy subject. Economic regulation is no different.

And now, the latest battleground is on the blockchain.

The Regulatory Gauntlet Is Thrown

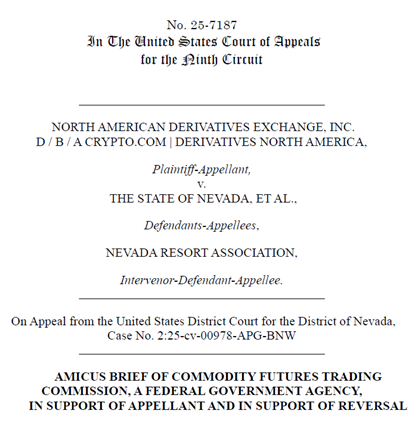

On Feb. 17, 2026, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) filed an amicus brief — a formal “friend of the court” filing — with in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The brief made one thing clear: The CFTC views prediction markets as firmly within its jurisdiction.

Now, its seeking to codify its understanding into law.

To push Project Crypto forward and clarify crypto regulation, new CFTC Chair Michael Selig is looking to clear up the confusion around predictive markets.

Specifically, he wants a clear answer on whether the event contracts predictive markets run on can quality as commodity derivatives per the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA).

If so, Selig claims that they then fall under the authority of the CFTC to regulate.

This is a strong shift from the status quo. As of right now, predictive markets are treated more like gambling outlets, especially where the outcome of sporting events are concerned.

That puts regulatory powers firmly in the hands of individual states.

And why several states currently stand in opposition to the federal government.

What Is a Prediction Market?

Prediction markets allow participants to trade contracts based on the outcome of future events. These contracts are also called “event contracts.”

They are the backbone of predictive markets. And most operate as binary contracts:

- $1 if the event occurs

- $0 if it does not

If a contract trades at $0.62, the market implies a 62% probability.

These markets have existed in limited academic and commercial forms for decades. What has changed in recent years is scale and accessibility.

Modern platforms now list contracts tied to elections, economic releases, policy decisions and sporting outcomes.

Just look at the Super Bowl.

DeFi Rate tracked the volume for Super Bowl pools on 68 platforms. Combining just the volume for the two top platforms, Kalshi and Polymarket, reveals an incredible $1.63 billion total.

For perspective, Kalshi alone saw over $800 million in volume, a 2,700% year-over-year increase just in one market.

With growth like that, a regulatory debate was only a matter of time.

The Legal Question: Derivatives or Gaming?

The dispute ultimately hinges on classification.

States contend that the event contracts tied to sports outcomes resemble unlicensed sports wagering, and that’s what they should be treated as.

However, the platforms argue that once the CFTC allows a contract under federal law, state interference is preempted.

The CFTC’s amicus brief asks the courts for an official answer.

- If prediction market contracts qualify as commodity derivatives, then CFTC jurisdiction applies.

- If they are deemed gambling products, then state regulators may assert authority.

This is more than just debating a dictionary definition. It’s a legal battle that can move a large amount of power out of the hands of states.

It could also open the door to more on-chain opportunities that U.S. residents have been kept out off for years now.

Kalshi: At the Center of Controversy

To be perfectly clear, the CFTC has not declared that all event contracts are permissible.

Rather, it argues that when a contract fits within the Commodity Exchange Act framework, federal law should govern the analysis.

While all predictive markets are eager for an answer, the first on the list is the one named in many of the ongoing lawsuits: Kalshi.

The platform operates as a CFTC-designated contract market (DCM) and has:

- Self-certified certain political and sports-related contracts

- Defended those listings in federal court

- Secured a favorable D.C. district court ruling related to election contracts

Kalshi maintains that its contracts are federally regulated derivatives, fully collateralized and operate under CFTC oversight.

Its legal argument centers on federal preemption. In simple English, if the CFTC says a contract is acceptable under the CEA, states cannot reclassify it as gambling.

That hasn’t stopped several states from trying to enforce their own regulations.

As of early 2026:

- Massachusetts ordered Kalshi to cease offering certain sports contracts within the state

- Nevada pursued enforcement actions and sought injunctive relief

- Tennessee and other states raised objections to sports-related contracts

Reporting in January 2026 indicated that Kalshi was involved in 19 federal lawsuits related to these disputes.

Appeals are underway in multiple circuits. The issue may even ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

Market Implications

At stake is not just the legality of specific contracts, but the broader question of how far federal derivatives law extends into event-based financial products.

If the Ninth Circuit Court rules in the CFTC’s favor, then we have a rough idea of what could come next.

The CFTC has indicated that upcoming rulemaking will clarify how specific provisions in the CEA apply to modern event markets. That includes …

- The scope of prohibited gaming contracts

- Public interest standards

- Market integrity and anti-manipulation safeguards

- Compliance obligations for platforms

The outcome will define the regulatory perimeter for event-based trading in the U.S. going forward.

And now is the time for this clarity.

Prediction markets have seen meaningful growth in participation over the past year. Particularly around elections and major sporting events.

If the U.S. can figure out how to regulate it, U.S. investors will be able to access their share of this impressive market before it’s done growing.

For now, prediction markets continue to operate, but under active legal challenge.

Which means, until the courts ultimately determine how the jurisdictional boundary is drawn, you’ll need to remain cautious when dealing with predictive markets.

Best,

Mark Gough