|

| By Nilus Mattive |

Warren Buffett just told the world that he will be “going quiet” after he steps down as the head of Berkshire Hathaway at the end of this year.

And I’ll certainly miss his annual shareholder letters, which were full of timeless wisdom.

Fortunately, we still have dozens of them to reference.

In addition, we can still see exactly what Buffett is thinking about the stock market right now … even if he doesn’t say a word at all.

Let me explain …

You might remember the fact that Buffett notoriously sat on the sidelines as the late 90s tech boom created massive amounts of wealth for other investors … at least temporarily.

Detractors everywhere suggested Buffett had completely lost the plot.

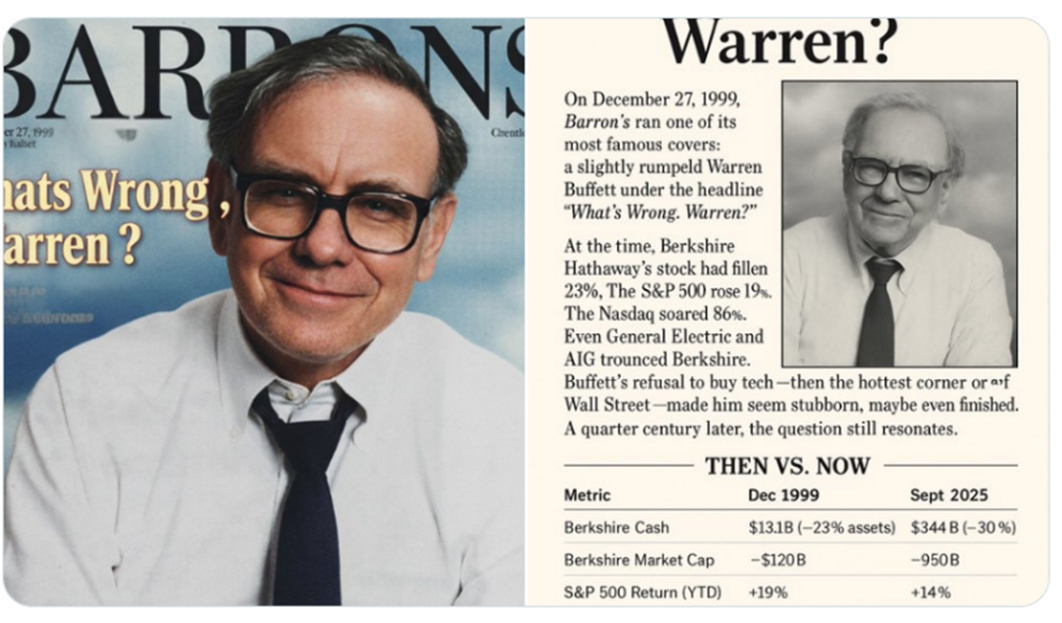

A now infamous December 1999 Barron’s cover story jokingly asked, “What’s Wrong, Warren?” after Berkshire Hathaway lost 23% versus an 86% rise for the Nasdaq.

So why didn’t he just jump on the bandwagon and ride the momentum for a while?

There was no way to know how long it would last.

And since Buffett couldn’t adequately project tech companies’ future business prospects, he simply decided it was better to wait things out.

Ultimately, Buffett was proven right. The fast gains turned into deep losses.

And guess what?

Today, Berkshire’s cash pile continues to grow to new record highs once again.

In fact, Berkshire has been a net seller of stocks for 12 straight quarters.

All told, the company now has about $382 billion sitting in cash and short-term securities.

That is your first inkling that good values are getting very hard to find and the market might be overpriced.

Buffett’s massive cash pile speaks volumes.

Of course, Buffett isn’t alone.

Last week, I told you why Palantir was yet another example of today’s “growth at any price” mindset.

Which is precisely why Michael Burry revealed that he was betting heavily against that particular stock (and others) before its earnings came out.

Burry’s last big contrarian bet against the housing bubble made him fabulously wealthy.

If you haven’t seen The Big Short about his exploits — or read the book behind the movie — I recommend doing so now.

Suffice it to say, like Buffett, Burry uses data and common sense to guide his decisions … he just happens to take a much more aggressive approach by using investments that directly profit from big collapses.

And what might the data show about stocks right now?

Just look at two broad-based measures of market valuations, both of which I often cite.

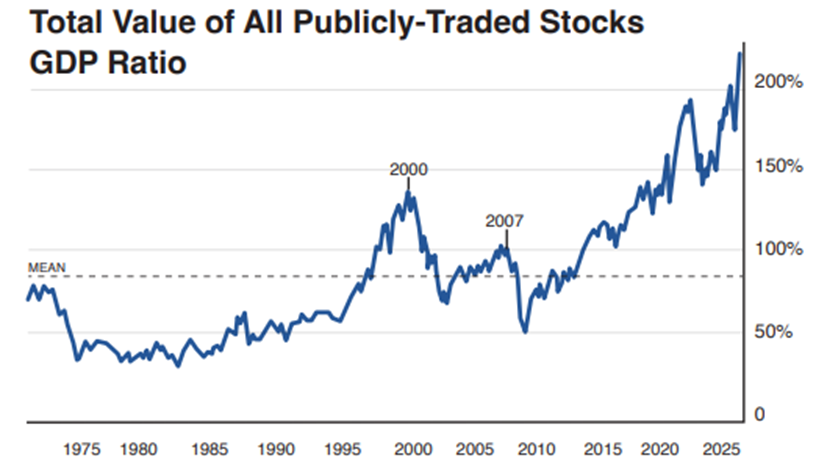

First, the “Buffett Indicator” — the entire value of the U.S. stock market divided by U.S. gross domestic product …

As you can see, we have now entered the most extreme reading in history … even higher than where we were the last time I discussed this metric with you.

Back in 2001, Buffett called this "probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment."

That was right after the indicator had topped out a staggering all-time-high level of 150% and a subsequent market crash had ensued.

Today, the same measure is moving solidly north of 200% for the first time in history — recently topping out around the 233% level!

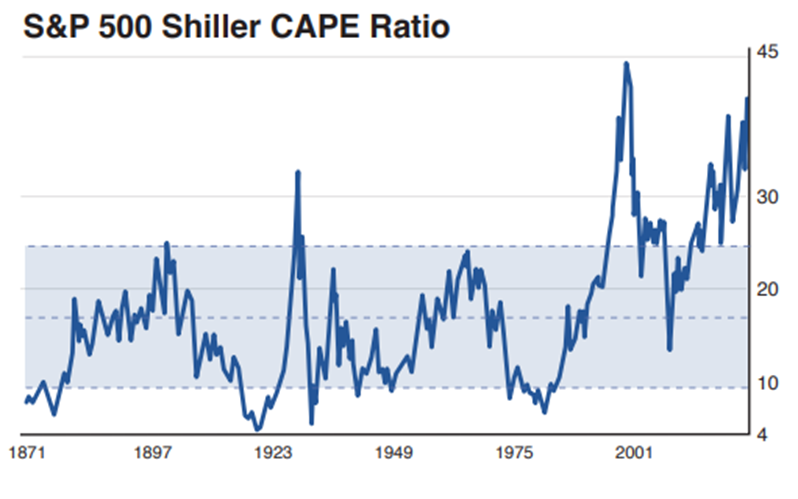

You will see the same basic thing if you look at another well-established measure that goes back to the Dot-Com Bubble days — Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, commonly called the CAPE.

The measure smooths out short-term volatility in company earnings to give a longer-term view of how much investors are paying for underlying businesses.

Here's the chart through Nov. 1 …

As you can see, we are perilously close to the all-time high last reached during — you guessed it! — the internet bubble.

Indeed, using data back to 1841, the CAPE only definitively surpassed a full standard deviation one other time in history: The late 1920s.

Could things go a lot higher still?

Absolutely.

Did last week’s little sell-off meaningfully change the big picture?

Not really.

So, should a rational person buy into this market heavily?

Absolutely not.

Consider yourself warned … again.

Better yet, prepare yourself with this.

Best wishes,

Nilus Mattive